Look for the Lights in the Sky

I met John Tedesco in 1976 when I was designing and building sets for the Plays in Progress series at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. He had just moved into a large warehouse space at 145 Bluxome Street and I was looking for scene shop space. John was a real born and raised New York City guy. He’d worked plenty of summer theater and at Four Star Lighting, the big rental company in the city. He was also involved in the early days of rock and roll touring. John moved west that bi-centennial year to set up his own lighting company in San Francisco. He called it The Phoebus Company and found a home for his new venture on the second floor of an industrial warehouse fronting a set of unused train tracks South of Market. The loading dock was boxcar height, with a 16’ roll up door and a large freight elevator. It was almost entirely empty. So we made a deal, and I moved our scene shop from Geary to Bluxome St. There was plenty of room.

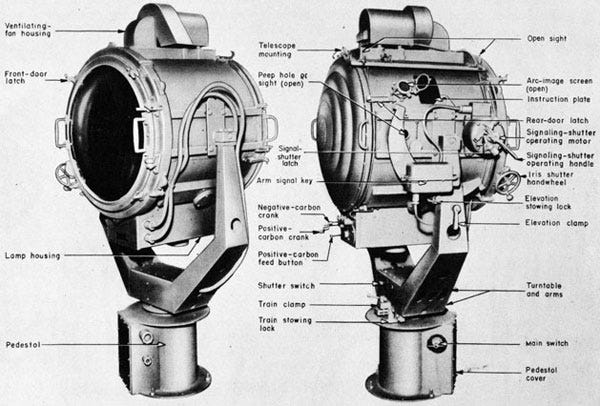

Phoebus didn’t have much inventory at first. John had made a name for himself in the early days of rock and roll touring- he’d done the lighting for Bette Midler and the Pointer Sisters and even an early Rolling Stones tour, so there were odds and ends in road boxes, but not much. What he did have was a collection of eight, 1940s era 24” Naval Searchlights he’d picked up at a surplus sale. Painted in a nasty Rustoleum yellow and mounted in rolling boxes, they stood on one side of the warehouse like a line of bedraggled sailors. These were carbon arc lights. They contained a mechanism that held and advanced a positive and a negative stick of carbon. When energized, an arc of electricity jumped the short gap between the carbons creating an intensely bright light. A highly polished Alzac reflector collated the light into a beam which could be seen, depending on the weather, for well over a mile.

Large Army searchlights were familiar to residents in the Los Angeles area. Originally developed for spotting enemy aircraft, they had giant 60” reflectors and their beams could be seen for miles. They were used all around the LA area to attract attention for movie premieres, grand openings, car lots and the like. The Army lights were big and cumbersome but smaller 24” Naval signal lights were ideal for what John had in mind. He intended to use them on stage for special effects.

The searchlights were obsolete. To work, they needed 1940s era carbon sticks, which were also obsolete, but John had located a source in Southern California and most of them had been restored to working condition. He had actually used a couple of them for an early Rolling Stones concert. The searchlights were hidden behind the stage and aimed straight up at a pair of 4’x4’ mirrors made from stretched mylar. These were attached to linear actuators, originally used to operate airplane flaps. They moved the mirror panels up and down, reflecting the super bright beams of light down onto the stage to backlight the Stones. No electronic controls in those days. You pressed toggle switches on a homemade plywood console to move the mirrors. Nobody had seen anything like it.

I soon moved from ACT to full time employment at Phoebus. I learned the ins and outs of keeping these World War Two relics in working condition. We could get two of them in the back of a pickup truck. and towing a DC generator, they would be perfect to advertise grand openings or clubs around San Francisco. South of Market was an industrial area and completely deserted after five o’clock. It was the beginning of the disco era and gay nightclubs began to proliferate in the neighborhood. Since there was no one around to complain, the clubs would stay open till dawn blasting disco tunes. Ever adaptable, Phoebus contracted to install lighting systems in many of these early clubs. Then we introduced them to our searchlights. Soon twin beams of light, crisscrossing the sky, marked their location and attracted patrons from across the city.

In the early days, in order to lift the lights off the loading dock and load them into the truck, someone would have to have to climb up to the roof of the warehouse with a radio and hand crank a cumbersome winch. Once loaded, the generator was hooked up and the rig was ready to go. Parking was always tight on the street. Patrons were supposed to reserve two ample spaces in front of their club and we’d have to back in, cranking the trailer into the narrow space. Several tries were often needed to get the truck in place and leveled on blocks. Once they were lit, the operator would sit on the sides of the truck between the two lights and give them a push to get them rotating. A job minimum was two hours, so pushing the lights was not very much fun. We soon rigged them with belt drive motors and from then on the lights would rotate (mostly) on their own. Then all we had to do was collect the check, not always and easy task.

One day in 1976, John had me get a searchlight ready to fire up inside the warehouse. The elevator arrived with it’s customary crash of the doors being lifted, and John ushered in a bearded, intense looking guy whom he introduced as Vilmos Zsigmond. Vilmos was a Hungarian cinematographer, and light meter in hand, he began taking readings of the searchlight beam. “One million candlepower!” he remarked, and made a note. Vilmos was photographing a film for a young director named Steven Spielberg, who was making a film called “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” Vilmos had an idea about using the searchlights as a signature for the alien ship. Off they went to a movie set to be used in several scenes. If you saw the movie, you will remember these scenes!

For the final scene, Vilmos had his grips suspend the searchlights above a reflective ramp, aiming down. The beams of light bounced off the ramp, creating an effect that silhouetted the aliens as they decended from their ship.

Searchlight jobs provided much needed extra income for a number of years. We cleaned off the yellow Rustoleum and painted the lights a glossy white. The two lights in our white pickup made a sharp looking rig and we had a regular stream of bookings. Three of us at Phoebus shared the operator responsibilities. We charged $225 for a two hour minimum, out of which the operator took home a hundred dollars. Decent money in the late 70s. The jobs were seldom dull. The probing beams of light attracted characters from all over the city who kept you company and peppered you with endless questions. “You looking for airplanes?” My new girlfriend Valerie would sometimes show up to wile away the hours with me. Looking for the lights in the sky, she would always know where to find me. We’d sit in the cab together and watch a tiny black and white TV that plugged into the cigarette lighter.

In the Spring of 1986, we got a call from the organizers who were planning the celebration for the re-dedication of the Statue of Liberty. Would we be interested in bringing our lights to New York to be part of the events planned for July 4th? John was from New York city so he knew the statue well, but for me, coming from a small town in California, it had always been a distant talisman. It’s image dotted my schoolbooks in the 1950s, more a symbol than a reality. To travel to New York city and actually set up lighting on Liberty Island was a dream some true.

By 1979 we’d outgrown our location on Bluxome street and moved further south on 3rd street. No more railroad car loading dock, no more rickety freight elevator. We had a couple of warehouses and a yard to work with now. When we loaded the truck for New York, we added a new type of searchlight. We had acquired four Skytracker units, each with four 2000 watt Xenon lamps. When they rotated, the beams described a four leaf clover pattern in the sky. Not quite as bright as the arc lights, they still had plenty of punch, and we included them for the Liberty Island setup. We also packed a number of single head Xenons to use as needed. The equipment filled a 45’ trailer. We waved good bye and good luck to Doug, our driver, and he set off on the cross country trek that would end on an island in New York City.

A few days later, John, Marty Axelson and I flew out to meet up with our equipment. We would be in the city for about two weeks, setting up and rehearsing for the extravaganza. There were multiple venues where celebrations would take place, with a large performance stage on the New Jersey shore and another in Central Park. A broadcast stage was set up on Governor’s Island, with a clear view of Lady Liberty across the water. There was activity on Ellis Island, and of course, Liberty Island itself was a beehive of preparation. Just about every lighting company in the New York area participated in some way.

We joined Doug as he drove the truck onto a barge at the Battery Park pier, and a short time later, disembarked beneath the statue herself on Liberty Island. This is where we were to spend our days. The barge was the only way out and back. It left in the morning and returned in the evening. Once on the island, we were stuck there until the barge departed.

The statue is immense. Seen from afar, or in pictures, it appears almost toylike, but standing beneath it was breathtaking. A gift from the French, it was erected on Liberty Island in 1886. In 1982, an engineering survey reported severe faults in the structure. The arm holding the torch swayed alarmingly in the wind and the copper armatures that held the body together were badly corroded. The statue was closed to the public. By 1984, a gigantic freestanding scaffold had been erectly, and repairs began. Two years later, Lady Liberty emerged triumphantly from her cocoon in time for her 100th birthday party.

There was no shortage of pessimistic naysayers among New Yorkers. The event was sure to be a disaster. There would be impenetrable traffic jams and rain would turn all the venues into seas of mud. People would trash the performance locations. All those private boats crowded together in the harbor spelled disaster. Wise locals would do well to leave town for the entire week of festivities.

Those who heeded this advice missed a once in a lifetime experience. July 4th dawned a beautiful day with clear blue sky and puffy white clouds. Traffic was moving well. The Central Park performance area had been left in tidy condition after the concert the night before. People picked up after themselves everywhere. One veteran N.Y cop remarked about the unexpected state of Central Park, “It was like it was your mom’s birthday. Nobody wanted to screw it up.”

Out on the island, we looked out, as did Lady Liberty herself, on an armada of boats in every size imaginable. As dusk approached, it seemed you might be able to walk from boat to boat all the way across the harbor. On Governor’s Island, President Reagan signaled for the festivities to begin by pressing a button that activated a green laser. It beamed across the harbor from the broadcast stage to the statue, and all hell broke loose.

Fireworks began shooting into the sky from a series of barges that ranged all the way down the East River. Then the large mortars surrounding our lighting locations on the island erupted. Never again would we see a sight like this.

The fireworks were loud and comprehensive. I found later that one of my shoe laces had been burned off. Banks of PAR cans bathed Lady Liberty in shimmering light, while the searchlights highlighted her face, book, and the torch she held aloft. The Skytrackers danced in the background, their clover leaf patterns etched in the smokey air. We heard, even above all the noise, the great cheer that erupted from every boat in the harbor.

It was my great fortune during my lighting career to have participated in many grand outdoor events, but nothing compares to this experience. Spending two weeks on Liberty Island with this towering symbol of America standing above moved me in a profound way. After the first day, we stopped thinking of the statue as “it” and began to think of her as “she.” Even growing up in far away Chester, California we had learned about this distant lady standing in the New York harbor. How she was the first thing so many immigrants strained to see as they arrived for processing at Ellis Island. But never had I imagined being this close. Me, celebrating Lady Liberty’s 100th birthday right there at her feet. Every day I spent on the island, I passed by the bronze plate affixed to her base and marveled at the words of Emma Lazarus memorialized there. We’d memorized them back in grade school.

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”